A golf club and a golf ball are two birds of a feather, but what was a “golf ball” when the club was just a wooden stick? The origin of the game of golf always has been and always will be a subject of controversy. Like stickball is to baseball, stick and ball games reminiscent of golf have been around for several centuries, with some accounts going all the way back to the Dutch in 1261. We will stick to our specialty, and concentrate on the history of the golf ball itself.

The question has always been about the materials, not so much the method. From the 13th century until the 17th century, hardwood beech and box trees were the first mediums conducive for the production of golf balls. In 1618, the “Featherie”, a feather golf ball (must have been great for birdies and eagles), made its debut. With the amount measured volumetrically by a gentleman’s top hat, goose feathers were tightly packed into a custom, cut-and-sewn horse or cow-hide sphere. In a lengthy process, feathers were boiled and compacted while still wet (the hide was wet too); then, as both dried together, the feathers expanded while the hide shrunk, resulting in a hardened ball. In today’s market, a “Featherie” would cost two to four times the amount of the most expensive new ball on the market now.

The question has always been about the materials, not so much the method. From the 13th century until the 17th century, hardwood beech and box trees were the first mediums conducive for the production of golf balls. In 1618, the “Featherie”, a feather golf ball (must have been great for birdies and eagles), made its debut. With the amount measured volumetrically by a gentleman’s top hat, goose feathers were tightly packed into a custom, cut-and-sewn horse or cow-hide sphere. In a lengthy process, feathers were boiled and compacted while still wet (the hide was wet too); then, as both dried together, the feathers expanded while the hide shrunk, resulting in a hardened ball. In today’s market, a “Featherie” would cost two to four times the amount of the most expensive new ball on the market now.

On to the next big medium—the dried sap of the Sapodilla tree. In 1848, Reverend Adam Paterson from St. Andrews in Fife, Scotland introduced the Gutta Percha or “Guttie”. With malleable sap that felt like rubber, the ball could be reshaped for more consistent flight. It was then discovered that nicks and grooves from normal wear and tear created more consistent flight than a new, smooth “Guttie”, and so began the invention of “brambles”, which are like crude, reverse dimples (they protrude from the ball instead of indenting). Because his employer was in the business of making "Featheries" Old Tom Morris actually was fired from his job at St. Andrews because he was caught playing with a "Guttie".

On to the next big medium—the dried sap of the Sapodilla tree. In 1848, Reverend Adam Paterson from St. Andrews in Fife, Scotland introduced the Gutta Percha or “Guttie”. With malleable sap that felt like rubber, the ball could be reshaped for more consistent flight. It was then discovered that nicks and grooves from normal wear and tear created more consistent flight than a new, smooth “Guttie”, and so began the invention of “brambles”, which are like crude, reverse dimples (they protrude from the ball instead of indenting). Because his employer was in the business of making "Featheries" Old Tom Morris actually was fired from his job at St. Andrews because he was caught playing with a "Guttie".

One day in 1898, a gentleman named Coburn Haskell happened to be picking up his friend, Bertram Work, from the B.F. Goodrich Company for a round of golf when he found some rubber thread, and decided to wind it into a ball. To their surprise, when it bounced, it almost hit the ceiling. Work suggested a cover, and so was born the 20th century “wound” golf ball, the Rubber Haskell. It was complemented by a thin outer layer of balata sap, a viscous liquid released from the balata tree, a native of Central and South America. With properties like the Gutta Percha, the sap gave the golf ball superior aerodynamics and playability.

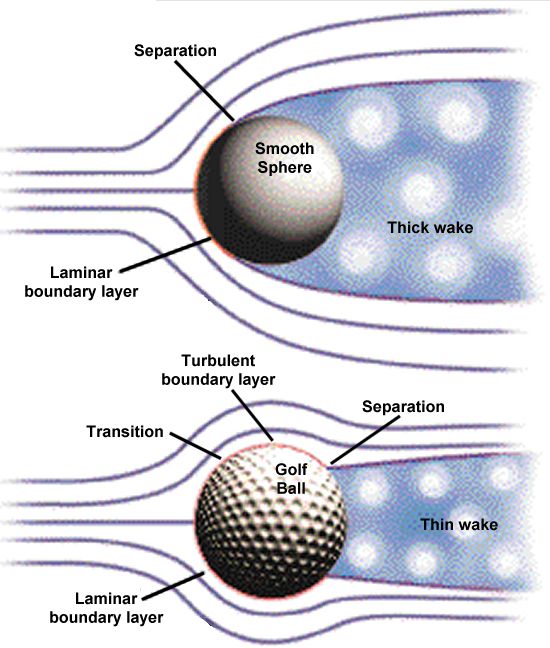

Throughout the early 20th century, there was ground-breaking innovation in design with regards to dimple structure. Dimples became inverted to allow circulatory air around the golf ball to create more lift and less drag, just like an airplane wing.

In the 1960’s, the Dupont Company invented Surlyn, a synthetic resin which was more durable than balata, and offered enhanced distance and playability for the average golfer. In 1972, when Spalding introduced the “Executive”, the first two-piece ball, the original 1898 design of the Haskell was on the upswing.

In the 1960’s, the Dupont Company invented Surlyn, a synthetic resin which was more durable than balata, and offered enhanced distance and playability for the average golfer. In 1972, when Spalding introduced the “Executive”, the first two-piece ball, the original 1898 design of the Haskell was on the upswing.

Since the seventies, countless innovations have been made in the realm of golf ball design and production, including the invention of solid-core golf balls, polybutadiene being introduced and urethane covers, making for the modern control and distance enjoyed today.

Because of these advancements, the golf ball industry no longer rates golf balls in terms of compression on a scale of 70 to 100, but rather bases the interwoven technology off of the perspective users swing speed. With variations of plus or minus seven points from ball to ball, the scale became very inexact and manufacturers got away from compression labeling. Red numbers used to indicate an 80 or 90 compression ball, and black numbers meant 100. The color of the number on the golf ball no longer conveys information about compression (nor does it convey any information at all).

Our industry has come a long way since the 13th century, and today (fortunately), you do not have to sew, cut, or pack your own golf balls. Thanks to Lost Golf Balls, you do not have to pay a lot for them or collect or clean them to feel the benefit of almost a millennium’s worth of golf ball enrichment. Like it was discovered that a ball with a few swings on it flies higher and farther than a new, smooth ball, it stands to reason that a recycled golf ball from Lost Golf Balls might fly better without as many dollar signs weighing it down.